byChrisWhite -2021

Thomas Jefferson, the Secretary of State at the time, was the one who called for the first decennial census. That was 1790. Every year ending in zero since, we’ve been counting heads, drawing invisible lines around lives. Births, trades, origins, occupations; little stories caught in government ink. I’ve spent the better part of two decades mining those records for roots, trying to understand how strangers became kin, how movement became memory.

The census isn’t perfect. Far from it. Uniformity is an illusion. Some marshals asked too many questions, some not enough. In Wilkes County, North Carolina, 1820, a man alphabetized his report by first name. Others wrote down counties of origin, a few added flair. These deviations, innocent or insubordinate, have become gold to people like me. Historians would call it inconsistency. I call it humanity.

The 1860 Nashville census was one such gem.

Nashville, that year, was straddling fire. The War of Northern Aggression crept closer into Nashville, Confederate officers strutted through dusty streets with a hunger no battlefield could cure. That hunger created an economy. And that economy left a trace. In 1860, census-takers counted prostitutes.

It wasn’t in their instructions. But they did it anyway. Perhaps they were nosy. Perhaps meticulous. Perhaps they just couldn’t ignore what they saw. For once, the world’s oldest profession wasn’t relegated to the backroom, it got column space.

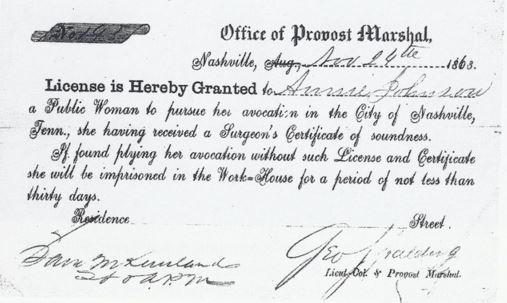

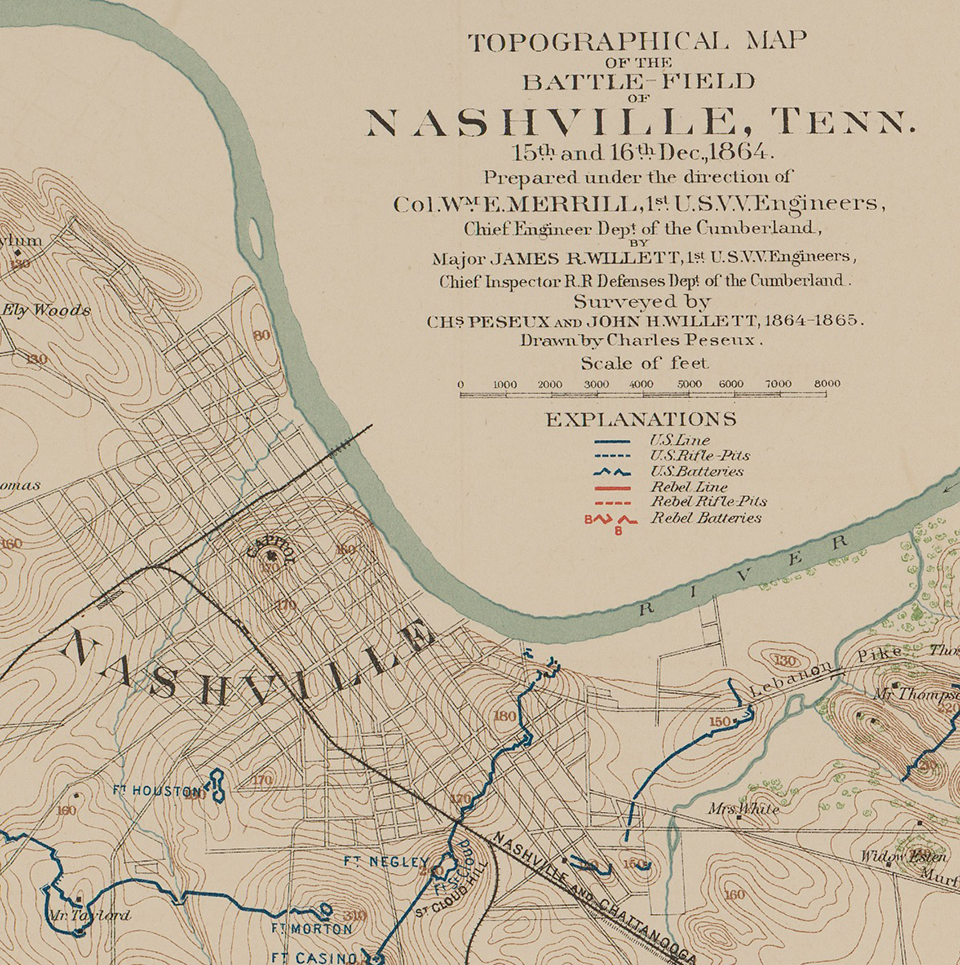

By 1863, venereal disease ran so rampant among soldiers that the city began licensing prostitutes and the houses that kept them. It was the first system of legal sex work in American history. Not Vegas. Not New Orleans. Nashville. Right there beside that lazy Cumberland River, the river that supported so much of the various economies along it, including an attempt at regulating this particular economy as I will explain.

It reminded me of Pompeii. Emily and I once wandered its ash-covered ruins, where the stones still whisper traces of that uncouth profession. Basalt roads carved with crude arrows, all pointing toward ancient brothels. Carvings of phalluses—testicles in-tact, half-erased by time but not forgotten. Some things never change.

Back in Nashville, the 1860 census recorded 207 self-identified prostitutes among 13,762 free residents. They listed their names and their lives: twenty-three years old on average, mostly white, mostly Tennessean. Nearly half were illiterate. Twenty said they were widows. Some called themselves seamstresses, one, a “Bagnio Keeper,” and even a “Tippling House Operator.” Others used no euphemism at all. There were undoubtedly then as now ladies of easy virtue whose income from legitimate sources was supplemented by funds received in return for services rendered, for favors bestowed, or in some other sense as a quid pro quo.

Nonetheless and despite all those shy types, there were still quite a few – I’ll say “professionals,” who were not at all reluctant to call themselves exactly what they really were – which totaled 207 out of the 13,762 free Nashville residents who reported in the 1860 census. Virtually all of them were white, although nine of them were listed as mulatto. Nearly half were illiterate; eighty-seven listed themselves as totally illiterate, and eight others arrogantly said that they could read but could not write. Twenty reported that they’d been widowed.

These otherwise virtuous women of Nashville ranged in age from fifteen to fifty-nine, although the majority were in their teens and twenties. Three were fifteen, 9 were sixteen, 15 were seventeen, 14 were eighteen, 12 were nineteen, and 10 were twenty. The mean age for these girls, however, was twenty-three, most of which were home grown. One hundred thirteen were Tennessee born and Kentucky and Alabama were tied for the dubious honor of second place, each furnishing 12 girls to the Nashville trade. In lesser numbers were women who hailed from Indiana, Massachusetts, Georgia, Virginia, Missouri, North & South Carolina, Ohio and Pennsylvania. Foreign born ladies were also represented; one woman hailed from Canada, and three came from Ireland where the potato famine was very recent history.

Emaline was not only one of those statistics of Nashville, she was also one of the first such women to get a professional license for vilified vocation when licenses became mandatory in 1863. Pretty Lula Suares, born in Pennsylvania, may have been of Spanish ancestry, and Jinnie Tante may have been French, but the other 205 had such names as Richardson, Scott, Johnson, Fox, Armstrong, Walker, Thomas, Graves, Harris, Patterson, Wilson, Webb, and Martin. The Browns were by far the most prolific, furnishing eight girls to the immodest trade.

Some names echo still: Eliza, Martha, Nancy, Mary—twenty-nine Mary’s, to be exact. The Brown’s gave us eight daughters to the trade. One house was run by the Higgins sisters on North Front Street. Rebecca Higgins, a madam, held real estate worth $24,000. Twenty-eight souls lived in that house—seventeen prostitutes, two children, a carpenter, a brick mason, and Tom Trimble, a twenty-two-year-old Black man whose story we’re left to imagine.

Most houses were humbler: one woman, two at most—widowed. Often with small children. Tragedy lived behind the doors. Poverty draped over windows like curtains no one washed. You could throw a dart at the Nashville map and find a heartache no matter where it sticks.

The area was known as Smokey Row. Four blocks long, two wide. Just north and south of Church Street, then called Spring. Front, Market, College, Cherry—they’re First, Second, Third, and Fourth Avenues (respectively) now. But the ghosts remain. They lived near the steamboat landing. Near business. Near soldiers.

Then came the Union.

In 1862, Nashville fell under occupation. The city swelled with federal troops. My second great-grandfather, John Wesley Milton Costellow, a Captain in the Union Army from Kentucky, among them. Disease followed them like a shadow. Eight percent were infected. Union General William Rosecrans wanted the problem gone. He ordered his provost marshal to seize every prostitute and send them to Louisville. All of them.

George Spalding found a steamboat, the Idahoe. Brand new. Maiden voyage. The irony didn’t escape anyone. One hundred eleven women were marched aboard. Every one white. Every one of them infected. The press had a field day. The Nashville Daily Union had something to say about it, its story unprintable today, but lectured the Union on how the departure of white prostitutes meant an immediate replacement with their black equivalents.

But Louisville refused them. So did Cincinnati. Kentucky wouldn’t have them either. For days, the women sat floating on the river, undesired in every direction.

They came back.

By the time they returned, the Idahoe’s staterooms were ruined. Bedding fouled. Newcomb, the boat’s owner, asked for $1,000.00 in compensation. Spalding, learning from failure, changed course. He legalized prostitution. Five dollars for a license. Fifty cents for a medical exam. Nashville, once again, became a first.

Among those licensed was the Emaline Cameron I introduced earlier. Born in Smithville. Pregnant at fifteen. Married off in haste. Divorced when truth surfaced. She fled to Nashville during the war, survived it, and returned home. Died years later in the house of her son. Her descendants walk this world not knowing how close history clings to them.

Most don’t.

They don’t know about Mag Seat’s house, staffed by teenage girls. Eleven prostitutes worked at Mag Seat’s place, address unknown. Mag was a twenty-five-year-old Tennessean who seemed to be able to keep a more youthfully staffed workshop than some of her other Nashville competitors. Six of her eleven girls were in their teens, and the oldest was twenty-four.

What about thirty-one-year-old Martha Reeder’s brothel at 72 North Front Street, where she reported owning $15,000 in personal property? Is it common knowledge that ten ladies of the night and two pre-school children lived there? They don’t know about Sarah Morgan and her three daughters—Rachel, Mary, and Nancy—all living together, all in the same line of work. They don’t know that “Mary Brown” might be more than a name.

Genealogy isn’t about the dead. It’s about the living.

This city once counted its whores—gave them paper and ink. And in doing so, gave them permanence. They weren’t just whispers in alleyways. For a time, they were acknowledged.

Then the war ended. The licenses vanished. The brothels faded—their girls, once forced into an awful trade in exchange for security, abandoned by husbands and fathers fighting a terrible war and now back home, their families unaware. But the records remain. And every now and then, someone like me digs them up and remembers. They get to live again.

Because behind every old census line is a human being. And some of them, whether we like it or not, helped build this city just the same.

Responses

Love it! Didn’t know you were such a history buff!! Actually, this is very interesting, reality with a bit of the White wit!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Greetings! I’ve been reading your website for some time now and finally got the bravery to go ahead and give you a shout out from Lubbock Texas! Just wanted to mention keep up the good work!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great blog! Is your theme custom made or did you download it from somewhere? A theme like yours with a few simple tweeks would really make my blog shine. Please let me know where you got your theme. With thanks

LikeLiked by 1 person

don’t know how I ran into this writing but I loved it!! So interesting.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you.

LikeLike